Late last year, Pegasus received all the buzz in the macOS/iOS scene. The spyware was used by nation state actors, targeting human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor. Developed by NSO Group in Israel, the malware is usually introduced via a malicious link through text message, and is capable of gaining remote kernel code execution on the target iOS device's before jailbreaking and installing itself onto the victim device.

Pegasus leverages 3 vulnerabilities collectively known as Trident-- a webkit memory corruption, a kernel infoleak, and another memory corruption in the kernel. Countless posts have been posted accompanied with proof-of-concepts for the kernel portion of Trident. This post isn't going to cover the details of the kernel exploits chain like the others. Instead, I just wanted to highlight and explain a minor detail in the infoleak portion that could cause some confusion.

Recall that the infoleak vulnerability resided in OSUnserializeBinary's big

switch case for kOSSerializeNumber where len is passed to initialize an

OSNumber, but is never checked.

case kOSSerializeNumber:

bufferPos += sizeof(long long);

if (bufferPos > bufferSize) break;

value = next[1];

value <<= 32;

value |= next[0];

o = OSNumber::withNumber(value, len);

next += 2;

break;Digging deeper down, we can see exactly how an OSNumber is initialized when

going through OSUnserializeBinary. In the snippet below, the actual value of

the OSNumber is obtained through the provided value logical anded with the

sizeMask. The sizeMask is a pound defined value in the beginning of the

file that that basically just masks out any bits not used by our value.

#define sizeMask (~0ULL >> (64 - size))

bool OSNumber::init(unsigned long long inValue, unsigned int newNumberOfBits)

{

if (!super::init())

return false;

size = newNumberOfBits;

value = (inValue & sizeMask);

return true;

}As I was trying to understand the Trident infoleak, I couldn't wrap my head

around how everyone was able to leak the return address of

is_io_registry_entry_get_property_bytes and, in addition, leak the OSNumber

value using a len of 0x200. For example, the output below is from my PoC

exploit.

[.] leaked data:

0x4242424241414141 <-- OSNumber value

0xffffff802c274584

0xffffff802c76c400

0x4

0xffffff80296245a0

0xffffff802c2745b4

0xffffff887e9e3e30

0xffffff801ed962cf <-- return addressQuoting the C++ standard (2014 draft) chapter 5.8:

The behavior is undefined if the right operand is negative, or greater than or equal to the length in bits of the promoted left operand.

Just to do a quick test, I ran

$ cat foo.cpp

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

printf("%#llx\n", ~0ULL >> (0x40 - 0x200));

return 0;

}

$ ./foo

0x7fff5a1fa6b8

$ ./foo

0x7fff532f26b8

$ ./foo

0x7fff5db0c6b8So naturally, I thought that the leaked data that corresponded to the

OSNumber value would just be garbage, but this was not what I was seeing. I

was seeing the whole 64 bits of constructed data. Perplexed but intrigued, I

decided to get to the bottom of this even though it doesn't really matter for

the actual exploit.

Shortly after I wrote the test program above, I realized that the compiler

might have optimized the program to not include the shift. If you disassemble

it, you can confirm that's indeed the case. Whatever was in the counter

register is actually passed as the second parameter of printf which is why it

looks like we're printing stack addresses. Instead of writing another test

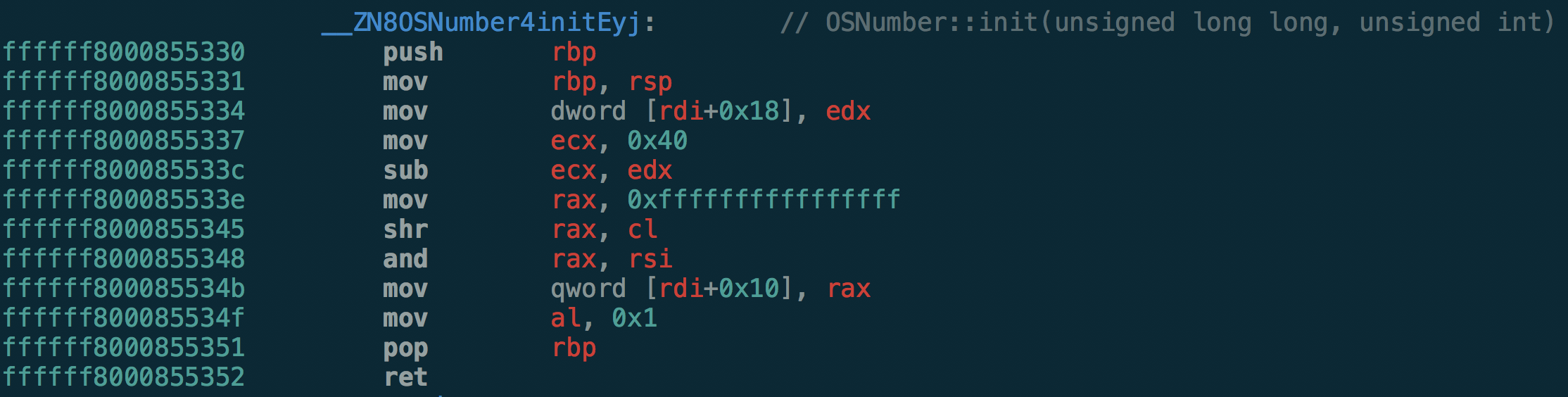

program, I decided to just take a look at the disassembled OSNumber::init.

Here, edx is newNumberOfBits which is assigned to size. ecx is 0x40

(64 decimal). ecx subtracts our size edx, and the least significant byte

becomes our shift count. After the subtraction, ecx should become

0xfffffe40 (0x40-0x200), and thus cl becomes 0x40 which is exactly the

bit length of an unsigned long long. Still, intuition would say that logical

right shift of the whole bit length would result in 0.

The behavior we're seeing is quickly explained when we look at Intel 64 and IA-32 architectures software developer's manual's section about SAL/SAR/SHL/SHR.

The count operand can be an immediate value or the CL register. The count is masked to 5 bits (or 6 bits if in 64-bit mode and REX.W is used). The count range is limited to 0 to 31 (or 63 if 64-bit mode and REX.W is used). A special opcode encoding is provided for a count of 1.

...

In 64-bit mode, the instruction's default operation size is 32 bits and the mask width for CL is 5 bits. Using a REX prefix in the form of REX.R permits access to additional registers (R8-R15). Using a REX prefix in the form of REX.W promotes operation to 64-bits and sets the mask width for CL to 6 bits. See the summary chart at the beginning of this section for encoding data and limits.

Indeed, the corresponding opcode is 48 D3 E8 which has the REX.W

prefix. Masking 6

bits means that an Intel processor will shift at most \(2^6-1=63\) bits before

cycling back to 0 shift count.

Modifying our original test program slightly, we can see this exact behavior.

$ cat foo.cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

printf("%#llx\n", ~0ULL >> (0x40 - atoi(argv[1])));

return 0;

}

$ for i in `seq 0 70`; do echo $i: `./foo $i`; done

0: 0xffffffffffffffff

1: 0x1

2: 0x3

3: 0x7

...

60: 0xfffffffffffffff

61: 0x1fffffffffffffff

62: 0x3fffffffffffffff

63: 0x7fffffffffffffff

64: 0xffffffffffffffff

65: 0x1

66: 0x3

67: 0x7

68: 0xf

69: 0x1f

70: 0x3fIn hindsight, shifting 0 bits obviously should produce 0xffffffffffffffff and

using 6 bit mask for 64 bit length also obviously makes sense. None of this has

any bearing on the Pegasus/Trident infoleak portion as long as the length is

greater or equal to 512; I just found this minor detail interesting.